By TechnologyAzure and AWS Monitoring

By IndustryIntegrates with your stack

By InitiativeEngineering & DevOps Teams

TechnicalIt’s easy to get the help you need

Who doesn’t love a little bit of data access? Most line-of-business applications are built over some sort of data storage, and nine times out of ten it is a relational database. SQL has a long and distinguished pedigree dating back to some time in the 1980s. Unfortunately, relational data doesn’t match the way we use it in object-oriented languages. To solve this mismatch, we developed tools called object-relational mappers (ORMs).

In this article, we’ll look at one ORM in particular: Entity Framework Core. We’ll cover the following topics.

For many years in the .NET space, the king of these tools was NHibernate, which originated in the ALT.NET movement. One of my favorite ORMs from the same ALT.NET era was Subsonic created by Rob Connery. Microsoft, not wanting to be left out, created their own ORM called LINQ2SQL, which was supported only for a couple of years, but has the distinction of being the ORM used to create StackOverflow. Microsoft put in a much more serious effort with Entity Framework. As with a lot of Microsoft products, the early versions were inferior to the community-supported ones. But the technology rapidly improved, and by version 4 Entity Framework was, in my opinion, at least as good as NHibernate.

For a while, all was good in the Entity Framework world. But then came the great revolution that was ASP.NET Core and .NET Core. As part of this change, the Entity Framework team decided that the current EF code base would not support the ambitions of an updated ORM. Thes ambitions included being able to talk seamlessly to different storage backends such as MongoDB and Redis. Entity Framework Core was created. EF Core is now at version 2.1 and is the real deal. Let’s look at how to use it.

The .NET ecosystem contains a few actively maintained ORMs. Dapper comes to mind as the most readily used alternative. Dapper is a micro ORM that really just provides for the mapping from result sets into entities; it has no ability to generate schemas or get you out of writing SQL. EF supports all of this and can mean that you don’t need to write a single bit of SQL in your application. The queries that EF generates are very good and even quite readable, if you do need to drop to SQL to debug. When you need to get an application off the ground quickly, EF provides a low-friction path for data access.

Before we dig too deep, let’s look at three of the major concepts in EF: the model, DbSet, and context. The most basic unit in Entity Framework Core is the model; you can think of a model as being a single row inside a relational database table. Models in EF are plain old CLR objects – that is to say, just classes with properties on them.

public class Ant {

public Guid Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public int AgeInDays { get; set; }

public string FavoriteAntGame { get; set; }

}

This class is a fine model. Notice that we have a property called Id on the model. While you don’t need to do this, it is a good idea to have an Id property that EF will automatically treat as the primary key for the table.

The next piece we need to know about is a DbSet. This is simply a collection that implements IQueryable in much the same way that a List does. There are some additional methods on the class that enable you to do updates you wouldn’t find on a simple IQueryable. DbSets are super powerful because you can work with them like you would any other collection. They can also be a source of performance problems because the abstraction away from the database allows for dramatically inefficient queries. You can think of DbSets as being tables in a database.

Finally, we have the DbContext that holds a number of DbSets which are related to each other. You can think of a DbContext as being the database proper or a schema within the database.

We’ve already started down the road of building a database around the concept of an ant hill so let’s go all in on that poor domain selection decision. Let’s add a couple of new entities to our the Ant we specified above. Perhaps a Queen and a Hive.

public class Queen

{

public Guid Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public int AgeInDays { get; set; }

}

public class Hive

{

public Guid Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public decimal LocationLatitude { get; set; }

public decimal LocationLongitude { get; set; }

public Queen Queen { get; set; }

public IList<Ant> Ants { get; set; } = new List<Ant>();

}

These classes are, again, pretty simple. One thing to notice is that we have a Queen and a collection of Ants hanging off the Hive object. These provide some relationship information for EF and make using the data much easier from an object-oriented perspective.

To make use of EF we’ll pull these various items into a DataContext.

public class Context : DbContext

{

public Context(DbContextOptions<Context> options) : base(options)

{

}

public DbSet<Ant> Ants { get; set; }

public DbSet<Hive> Hives { get; set; }

public DbSet<Queen> Queens { get; set; }

}

If your application is a ASP.NET Core web application, then to start using the context you just need to register it in the services collection

services.AddDbContext<Context>(options =>

options.UseSqlServer(Configuration.GetConnectionString("DefaultConnection")));

This will use the default connection string from the configuration provider. In our example, we’re writing a command line application so we need to provide some of this configuration ourselves. To do so we can make use of the options builder

var optionsBuilder = new DbContextOptionsBuilder<Context>();

optionsBuilder.UseSqlServer("Server=(local);Database=hive_develop;Trusted_Connection=True;");

var context = new Context(optionsBuilder.Options);

In a normal scenario, you’ll want to get that connection string from a configuration source.

Frequently I see applications that keep dozens or hundreds (eeek!) of DbSets within a context. This is a bad plan because it encourages creating hyper-complex queries that span a lot of entities. You’re better to take a page out of the domain driven design book and treat each context as a bounded context. Julie Lerman, speaks of this in her data points article from way back in 2013.

Now we’ve got a context, let’s start making use of it. The first thing we’ll want to do is lean on Entity Framework to create our actual database. This can be done as simply as calling:

await context.Database.EnsureCreatedAsync()

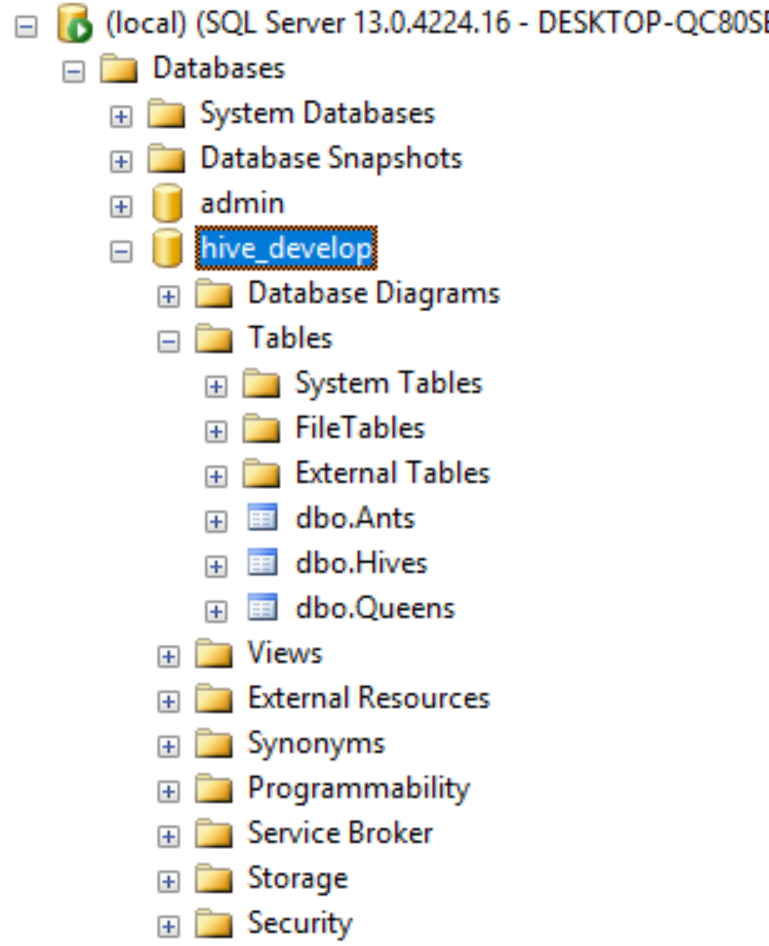

The result of this is a database created in the instance from the connection string that we set above

As you can see, the database and tables are created. If we were to drill into the Hive table, we’d see that it has a foreign key relationship to Queen, which Entity Framework Core figured out by just looking at our classes. This is the simplest approach to building a database; however, for more complex and real-world scenarios, you’ll likely want to make use of a concept called Migrations. Migrations provide a mechanism for updating your database as the application evolves. They can be run outside of your application proper as part of a deployment pipeline, and also help when multiple developers might be making changes to the database at the same time.

One of the things that make Entity Framework Core such a powerful ORM is that it has first-class support for LINQ. This makes simple queries remarkably easy to execute. The DbSet in the context implements an interface called IQueryable, which allows you to chain function calls together to filter, project, sort, or any number of other things. Let’s try a few quick examples:

Get all the ants named Bob (a very popular name ant name):

context.Ants.Where(x => x.Name == "Bob")

You can also do compound queries where you provide multiple constraints. Here we want all the ants named Bob who are older than 30 days.

context.Ants.Where(x => x.Name == "Bob" && x.AgeInDays > 30)

Because all these queries are implemented using expressions you can build up queries and only have them execute when you request results from them. So, for example, we can build a search engine style query like so.

private async static Task<IEnumerable<Ant>> Search(Context context, int? age, string name, string game)

{

var query = context.Ants as IQueryable<Ant>;

if (age.HasValue)

query = query.Where(x => x.AgeInDays == age);

if (!String.IsNullOrEmpty(name))

query = query.Where(x => x.Name == name);

if (!String.IsNullOrEmpty(game))

query = query.Where(x => x.FavoriteAntGame == game);

return await query.ToListAsync();

}

This allows passing in a number of parameters, some of which may be null. As you can see, we build up a query in a highly readable and scalable fashion. The IQueryable may be passed around to any number of builder functions, each one of which stacks up some further criteria.

Of course, we can do more than just filter data using EF: data can be sorted, projected, or combined in a myriad of ways.

LINQ is a really nice domain-specific language for manipulating and querying objects, however, sometimes you have to relax the abstraction and get back to the relational model. If you find yourself building crazy queries that bend your mind with the complexity of the LINQ, then take a step back: you can drop to SQL to perform your queries.

This is done using the FromSql for queries:

context.Ants.FromSql<Ant>("select * from ants");

or using the ExecuteSqlCommandAsync:

context.Database.ExecuteSqlCommandAsync("delete from ants where name='Bob'");

Unfortunately, you must use a real entity for your SQL queries and you cannot use a projection. This was functionality that was available in EF and will hopefully resurface in EF Core at some point soon. The recommendation in the Entity Framework Core documentation is to use ADO.NET, like some sort of peasant from 2003. Instead, I’d suggest you make use of Dapper, which does support mapping arbitrary data to objects. It isn’t a fully fledged ORM, but it does have the advantage of being very fast and very tunable.

Changing data retrieved from the context is really easy, thanks to the fact that all the entities used are tracked. If we wanted to load an Ant and then change the name, it is as simple as:

var ant = await context.Ants.FirstOrDefaultAsync(x => x.Id == id); ant.Name = "Bob"; await context.SaveChangesAsync();

You’ll notice that Entity Framework Core has a lot of asynchronous methods – they’re the ones ending in Async. These methods are generally a better option than the synchronous ones for applications that need to run multiple database queries at once. You should be aware that async does add some overhead, so it is not universally superior. Benchmarking is really the only solution.

Entity Framework Core maintains a memory reference for every object retrieved from the database in order to know what has changed when writing records back. In many scenarios, especially web scenarios, there is no need to maintain this information because the entities you’re saving are rehydrated from an HTTP request. You can make EF Core much more efficient by setting no tracking:

var ants = context.Ants.AsNoTracking() .ToList();

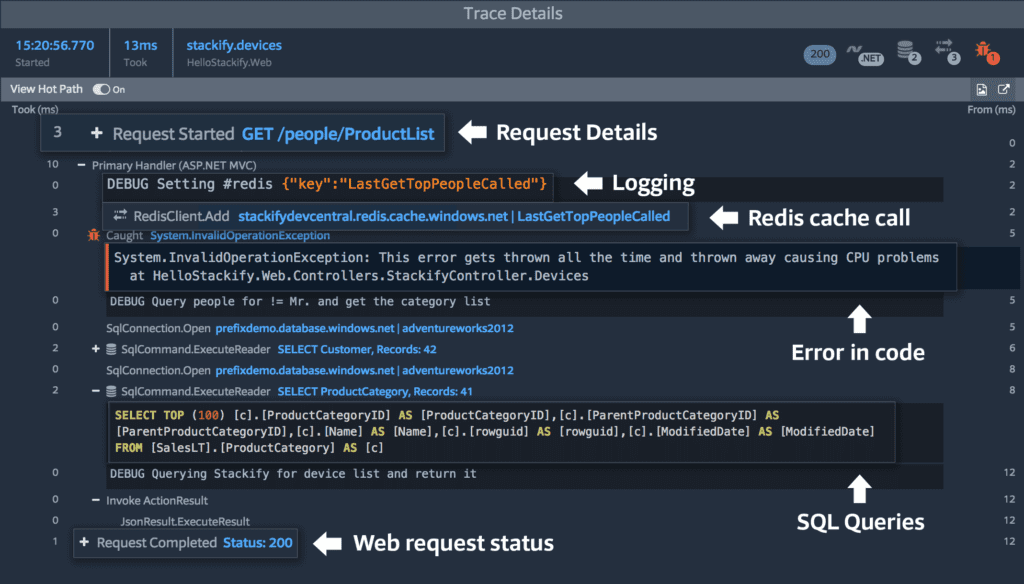

You can easily build queries in Entity Framework Core that seem reasonable, but end up being very costly when transformed to SQL. In order to watch the queries you’re making, there is no better tool than Prefix. You can use Prefix to spot common issues like n+1 problems or slow queries. Your users will be grateful that you’ve taken the time to install and run some profiling. And the best part is, Prefix is free. Download it here.

Read more:

How to View SQL Queries from Your Application Code with Prefix

Performance Tuning in SQL Server Tutorial: Top 5 Ways to Find Slow Queries

Stackify's APM tools are used by thousands of .NET, Java, PHP, Node.js, Python, & Ruby developers all over the world.

Explore Retrace's product features to learn more.

If you would like to be a guest contributor to the Stackify blog please reach out to stackify@stackify.com